Stories of Yampa Valley’s Past

Content courtesy of Museum of Northwest Colorado in Downtown Craig

From Labor to Lifestyle: Howelsen’s Impact on Skiing

Skiing was a common form of winter travel for early trappers, prospectors and homesteaders to the area. Mail carriers even skied the mail from Hot Sulphur Springs and Laramie in the 1870s and 1880s. But it was the 1913 arrival of Norwegian brick layer and celebrated skier, Carl Howelsen, that transformed local skiing into a recreational mainstay. In addition to dazzling residents with his jaw-dropping ski jumps, Howelsen also organized Steamboat’s first official Winter Carnival in 1914 and laid the foundation for the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club. He also constructed the first ski jump on the hill now named in his honor. Howelsen’s impact even reached downriver to Craig, CO where he occasionally trained. His skis are currently on display at the Museum of Northwest Colorado in Downtown Craig (pictured).

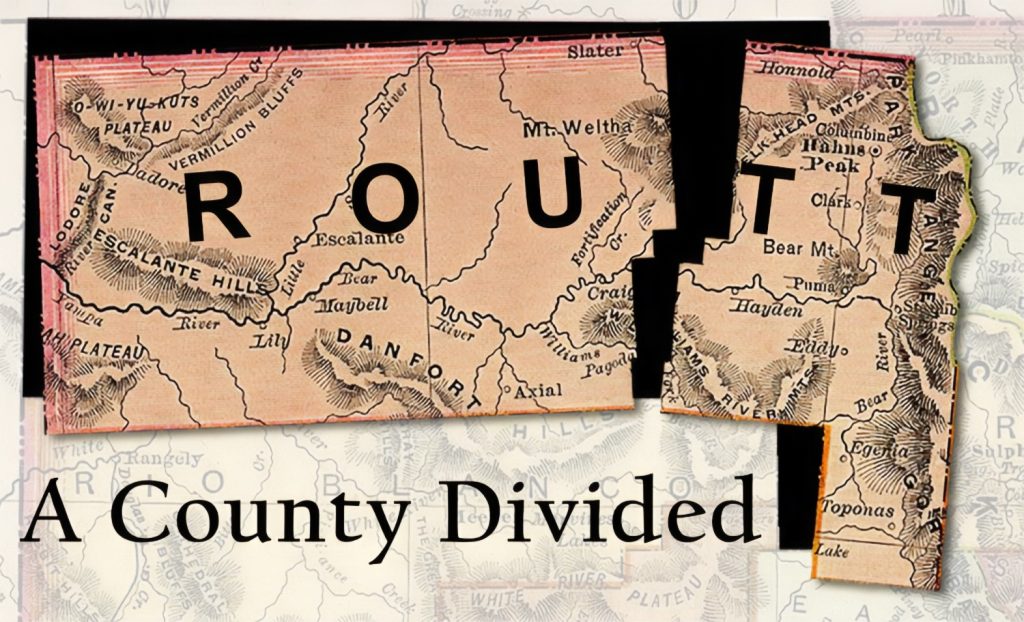

A County Divided

Most people are surprised to learn that Routt County once consisted of both Routt and Moffat Counties combined. Routt County was officially formed in 1877 with the gold camp of Hahns Peak (the largest voting population at the time) as county seat. Unfortunately, Hahns Peak’s major gold was mostly played-out and the population quickly dwindled. It wasn’t long before the rest of the massive, 125-mile-wide county clamored for a closer, more accessible location. However, there was one problem: Steamboat, Craig and Hayden all felt they should be county seat and no vote to move it ever reached the necessary threshold. Finally in 1911, after over 3 decades of bickering, it was decided that there was only one way to solve the problem: a new county of Moffat was formed with Craig as the county seat while Routt County’s seat moved to Steamboat Springs.

ABC’s & S-Turns

Few communities can claim that skiing was once as fundamental as math or history—but in Steamboat Springs, the slopes were part of the classroom. In 1944, skiing officially became a regular part of the public school curriculum for students from first through twelfth grade. Children received two hours of skiing instruction each week: grade schoolers during lunch breaks, and junior and senior high students after school at Howelsen Hill.

The curriculum spanned slalom, downhill, jumping, and cross-country. Al Wegeman and Olympian Gordy Wren led the program, teaching such notables as Buddy and Skeeter Werner and Marvin Crawford.

This unique chapter in Steamboat’s education proves that skiing wasn’t just a pastime—it was a way of life, taught as surely as any subject in school. In fact, fourth-generation Steamboat native Ray Heid jokes that it was the only “A” he ever received!

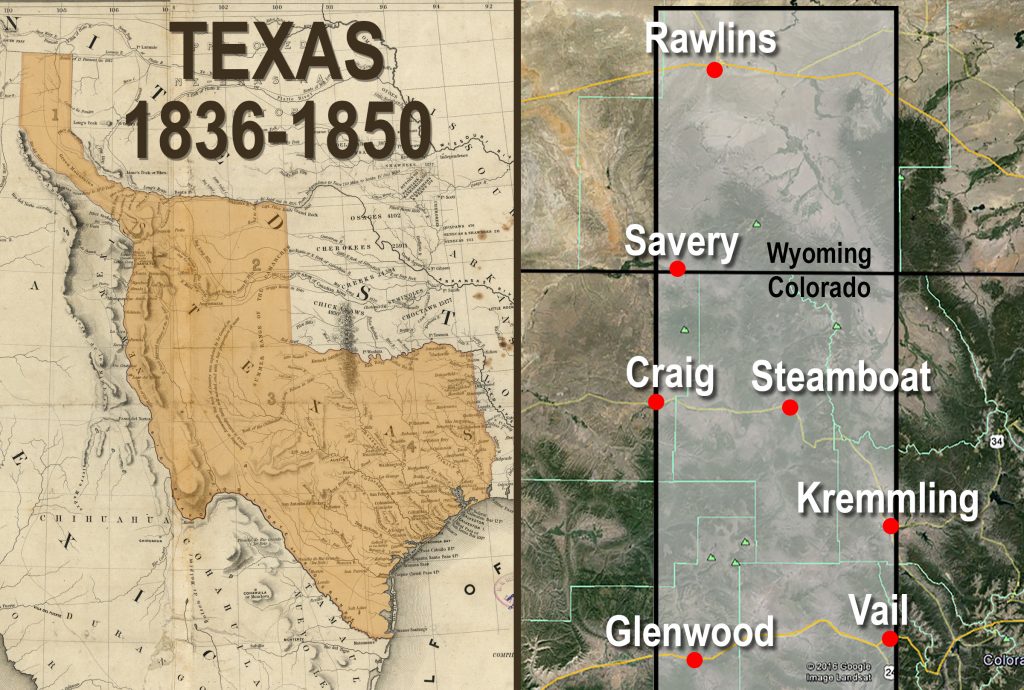

Far From the Heart of Texas

Believe it or not, there exists a wide swath of land running through the Yampa Valley that was once claimed by Texas. This included ALL of today’s Routt County and a portion of Moffat County. But why?

When the Republic of Texas declared independence from Mexico in 1836 (remember the Alamo?), they contentiously laid claim to an ambitious stretch of Mexican land as far north as today’s Rawlins, WY. The claim ended with the Compromise of 1850 at which time the Yampa Valley became part of Utah Territory. Then, in 1861, the mineral-rich Territory of Colorado was formed and has remained ever since. While no Texas Ranger ever rode through the Yampa Valley, this rugged landscape did once carry the Lone Star’s name, as both a nation and a state, for 14 years.

Steamboat’s Silent Film Company

In the early 1900s, Northwest Colorado had the usual small-town businesses—hardware stores, livery stables, groceries, and restaurants. What it rarely saw was a movie company. Yet in 1919, the Art-O-Graph Film Company, with offices in Denver and a studio in Englewood, chose Steamboat Springs for its silent film Wolves of Wall Street. The Steamboat Pilot described daring stunts in Brooklyn’s saloon district, coal miner strikes, and even building explosions at Mt. Harris. Pleased with the area, Art-O-Graph moved its executive offices to downtown Steamboat (908 Lincoln Ave) and scouted locations across Routt, Moffat, and Rio Blanco counties. Their next film, The Desert Scorpion (1920), featured locals as extras, a cattle stampede, and a scandalous romance between a sheepherder and a cattle king’s daughter. Between 1919 and 1923, the company shot about ten films before ultimately folding.

*The included photo is during the filming of Wolves of Wall Street and shows Art-O-Graph’s head office which is today’s Steamboat Shoe Market

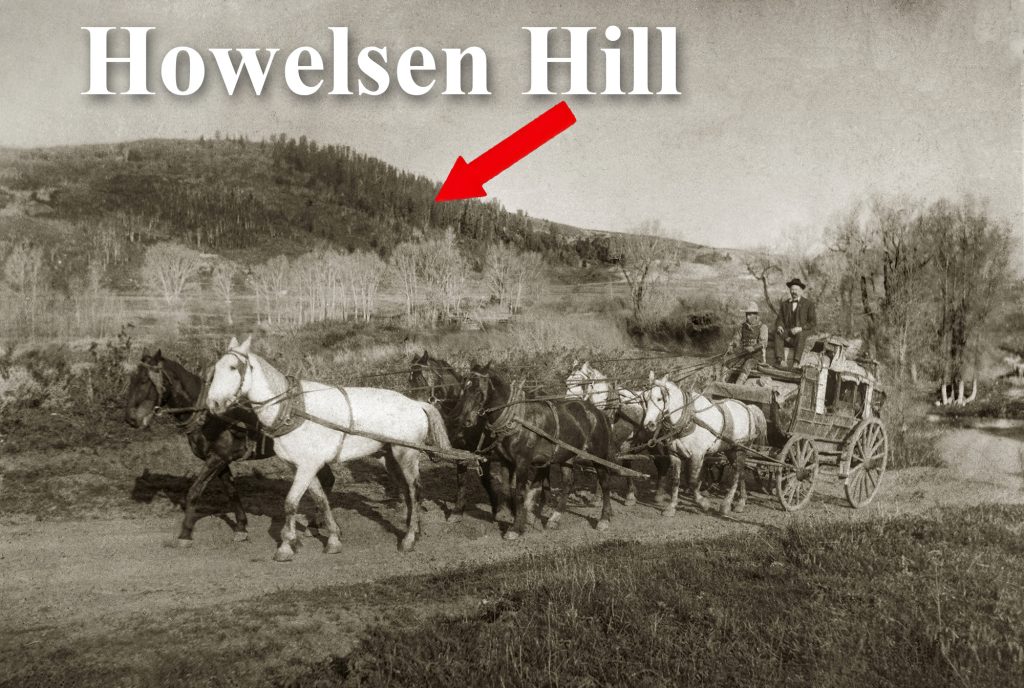

Last Stand of the Stagecoach

Northwest Colorado was among the last regions in the U.S. to rely heavily on stagecoaches. In the Yampa Valley, they remained essential until about 1915. The arrival of the railroad into Steamboat Springs in 1908, and later into Hayden and Craig in 1913, signaled the decline of horse-drawn travel, yet stagecoaches were still needed to reach outlying communities like Hahns Peak, Maybell, and Meeker. By 1915, the automobile delivered the final blow, and stagecoaches slipped into history. Stage travel was hardly cheap—far from it. In modern dollars, a round-trip ticket between Craig and Steamboat Springs would run about $275. The trip itself was grueling, requiring roughly 9.5 hours each way. Today, the same journey by car takes only 45 minutes, a reminder of just how dramatically transportation has evolved in a little more than a century.

*Photo was taken across from the Downtown Health & Rec pool in 1907

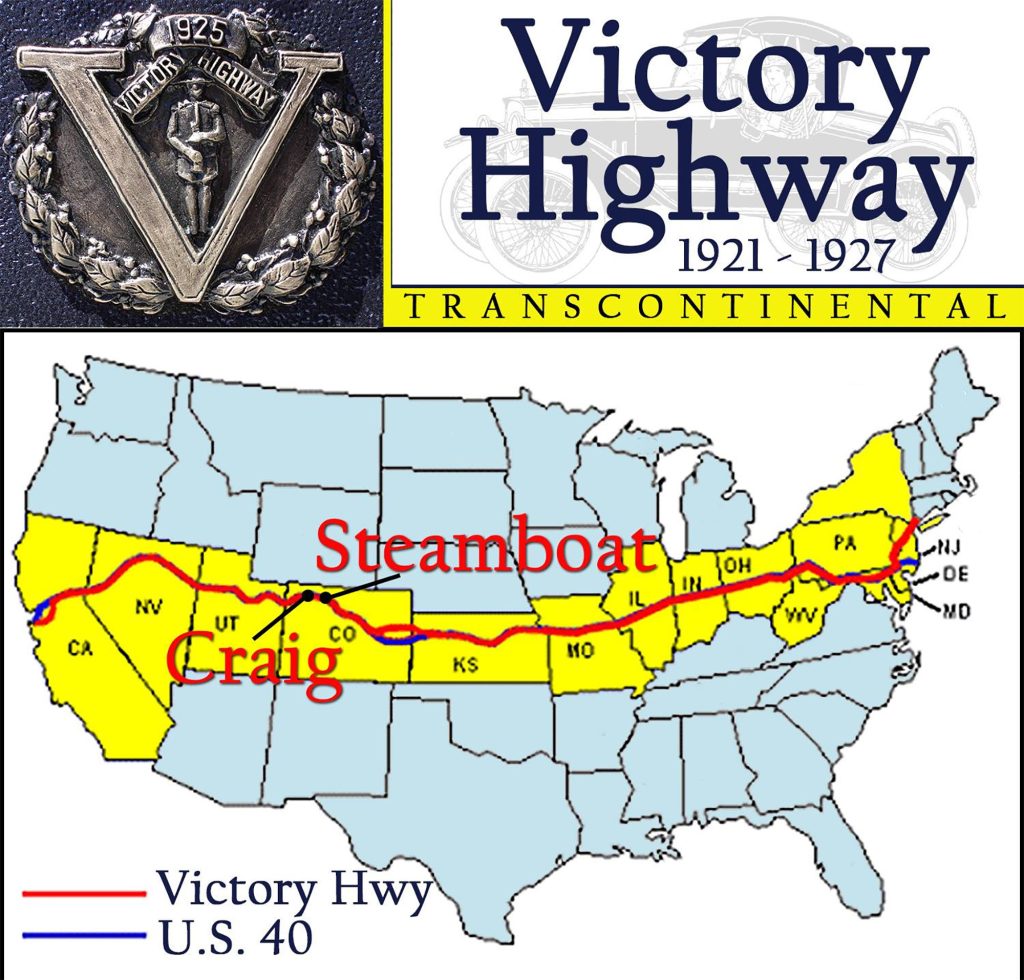

Hwy 40: The Old Victory Highway

After World War I ended in 1918, millions of returning soldiers embraced the dream of automobile ownership. Cars surged in popularity, but America’s road network remained little more than old wagon trails. That changed in 1921 with the creation of the Victory Highway Association, which sought to build a modern transcontinental highway honoring WWI service members. The “Victory Highway” would span New York to San Francisco, passing directly through Northwest Colorado along what is now U.S. 40. Almost overnight, gas stations, motels, restaurants, and tourist shops sprang up to welcome travelers. Local newspapers buzzed with excitement; a 1921 Pilot article declared, “You think you have good tourist travel now—wait until next year… all the autos in the world are going through Maybell.” In 1927, the route was officially designated U.S. Highway 40. In Craig, it still bears the name “Victory Way.”

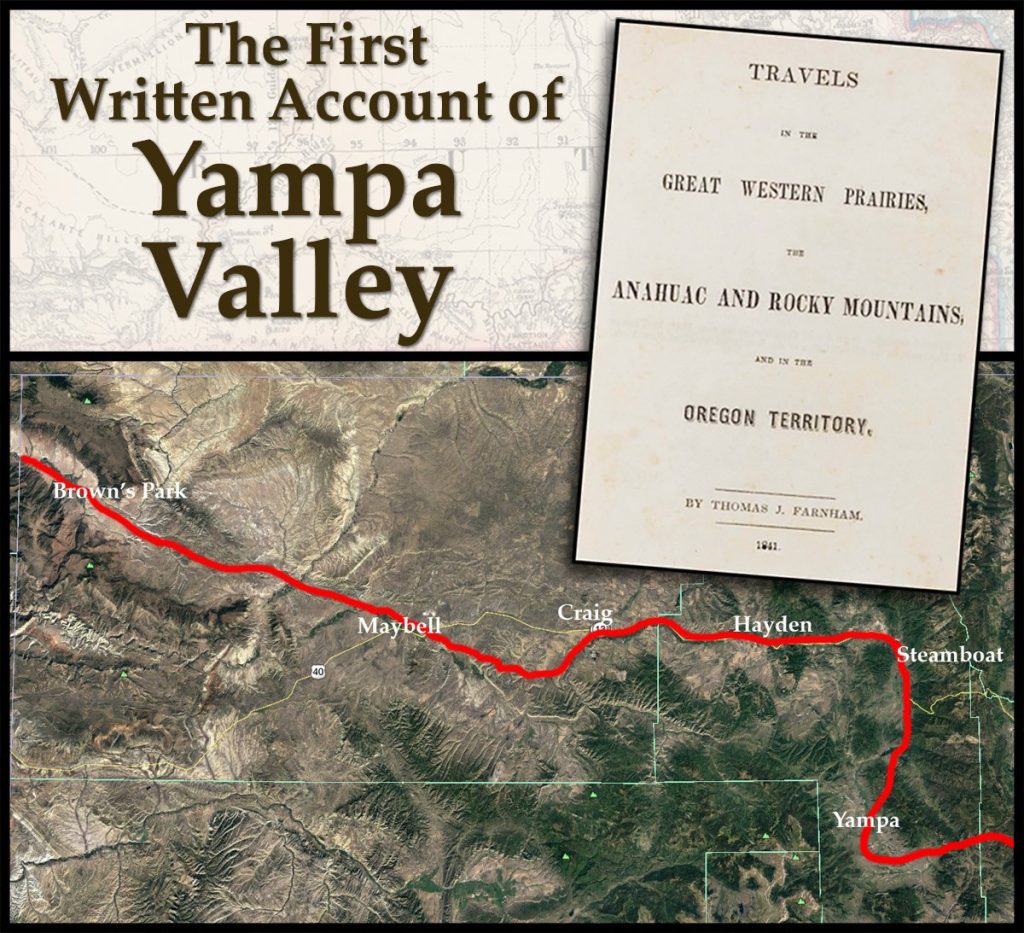

First Written Account of Yampa Valley

The first written account of the Yampa Valley in 1839 is a stark reminder of the hardships faced by those venturing beyond civilization. Thomas Jefferson Farnham left Illinois with 19 men bound for Oregon but chose a southern route through Colorado. Near mutiny reduced his party to a few men and a loyal dog. On July 31, they reached Egeria Park near present-day Yampa, describing Finger Rock and the valley’s beauty. By August 4, they were in Steamboat Springs, exploring Sulphur Cave and its hot springs. Scarcity soon forced them to kill and eat their dog near Maybell. Farnham lamented the barren land until relief came on August 13 at Fort Davy Crockett in Brown’s Park. His 1841 book Travels in the Great Western Prairies recorded both suffering and the earliest published description of the Yampa Valley.

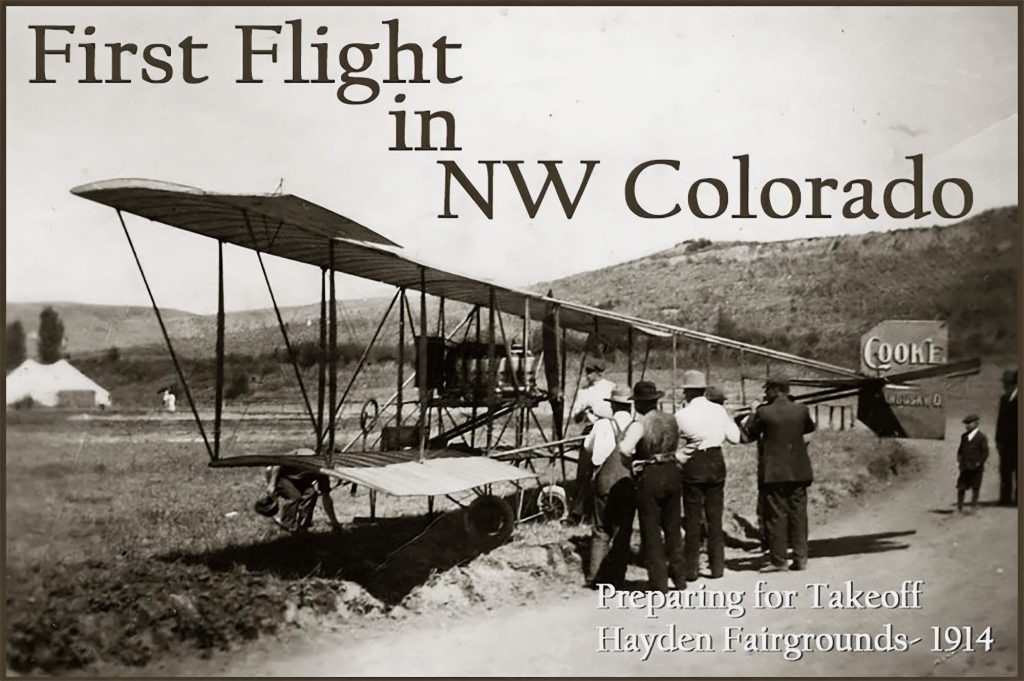

NW Colorado’s First Plane

In autumn 1914, the first Routt County Fair in Hayden offered something unforgettable: the region’s first airplane flight. Only 11 years after the Wright brothers’ achievement, few had ever seen a plane, let alone witnessed one fly. Fair organizers raised $650 (about $16,000 today) to bring aviator Weldon B. Cooke to Northwest Colorado. Nearly 2,000 people—far more than Hayden’s 350 residents—gathered to watch. Among them was 12-year-old John Rolfe Burroughs, who later described the aircraft narrowly clearing fences and poles before soaring above the Yampa River. The crowd erupted in awe, chasing the aviator to shake his hand. Tragically, Cooke died just a week later in Pueblo, though he had recently set a Colorado record for longest high-altitude flight. For those at the fair, his daring feat marked a turning point: proof that humans could share the skies with birds.

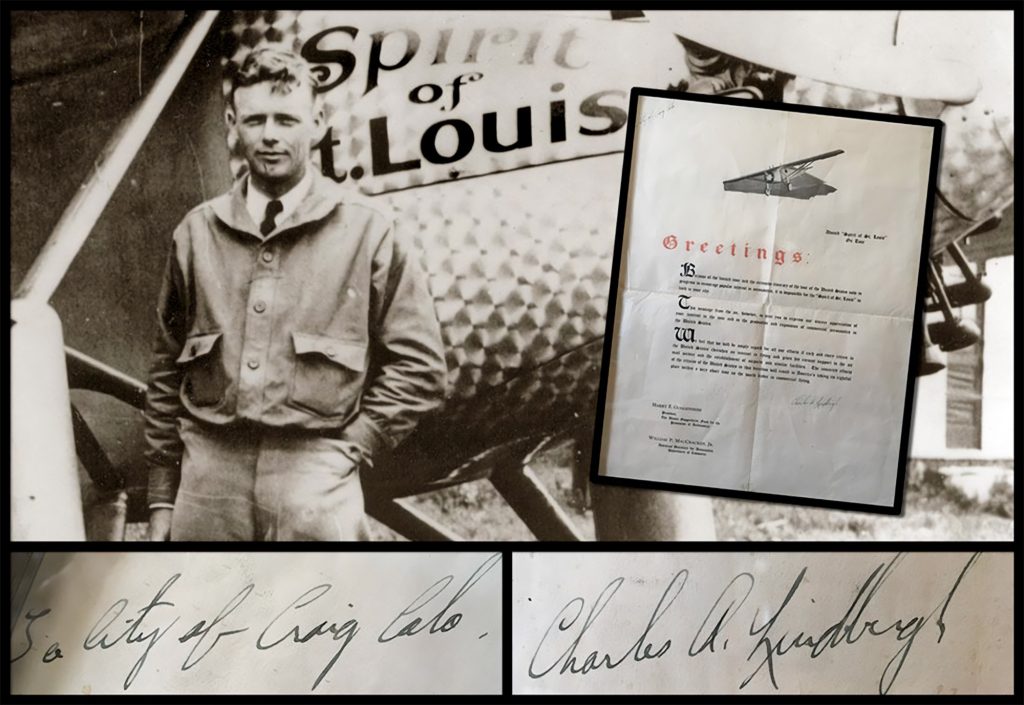

Lindbergh Buzzes NW Colorado

On a quiet Saturday morning in 1927, Craig, CO residents were startled as a low-flying plane suddenly swept down Yampa Avenue. Thirteen years after northwest Colorado first saw an airplane, this one felt different. The pilot banked sharply, made repeated passes, and dipped lower each time. Observers soon spotted the number N-X-211 beneath the wings—followed by the unmistakable words Spirit of St. Louis. Astonished onlookers realized the world’s most famous man, Charles A. Lindbergh, was flying just overhead.

Only four months earlier, Lindbergh had achieved his historic solo flight across the Atlantic, becoming an international hero celebrated by millions. Now on an 82-city national tour promoting his new book, he had departed Cheyenne that morning for Salt Lake City. On his sixth pass over Craig, he dropped a handwritten message addressed to the city—a signed note that survives today in the Museum of Northwest Colorado.

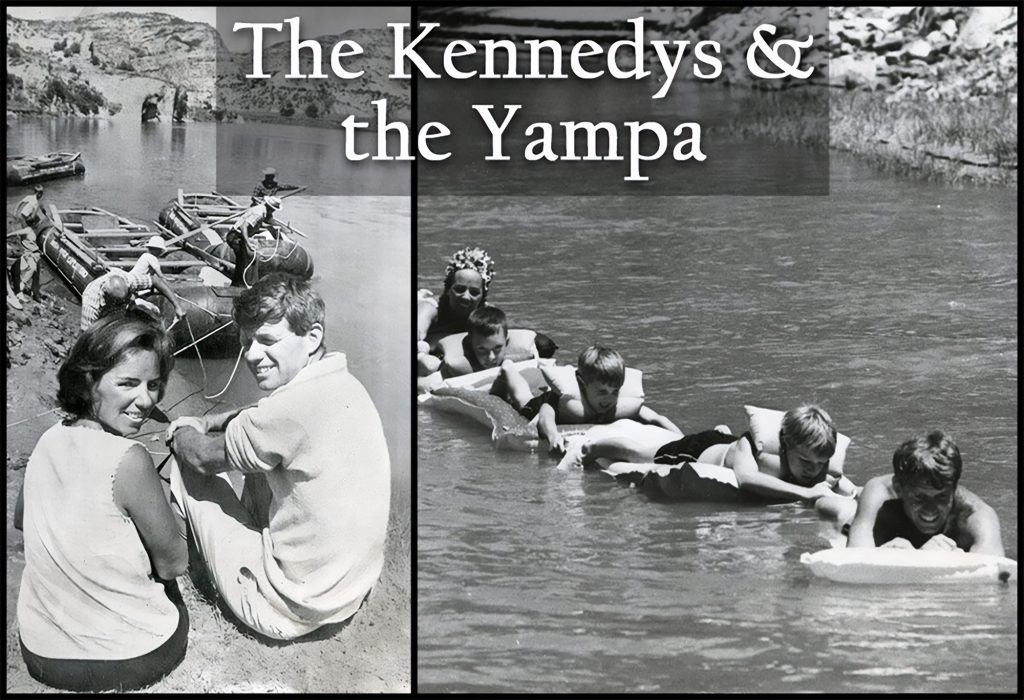

The Kennedy’s & The Yampa

Spotting an international celebrity is memorable; spotting several in a remote corner of NW Colorado is truly remarkable. In the mid-1960s, few names were more recognizable than the Kennedys. After President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Robert F. Kennedy quickly became the family’s leading figure, drawing national attention wherever he went.

In early 1965, just months after taking office as a U.S. Senator, Bobby joined famed climber Jim Whittaker—the first American to summit Everest—on a successful first ascent of Canada’s newly named Mount Kennedy. A few months later, Bobby, his wife Ethel, five of their children, and the Whittaker family traveled west again.

On July 2, 1965, they arrived in remote Lily Park to begin a three-day float down the Yampa and Green Rivers. Despite the isolation, major news outlets and roughly 200 spectators watched them launch. The Kennedys finished their trip with a visit to Dinosaur National Monument before flying on to Salt Lake City.

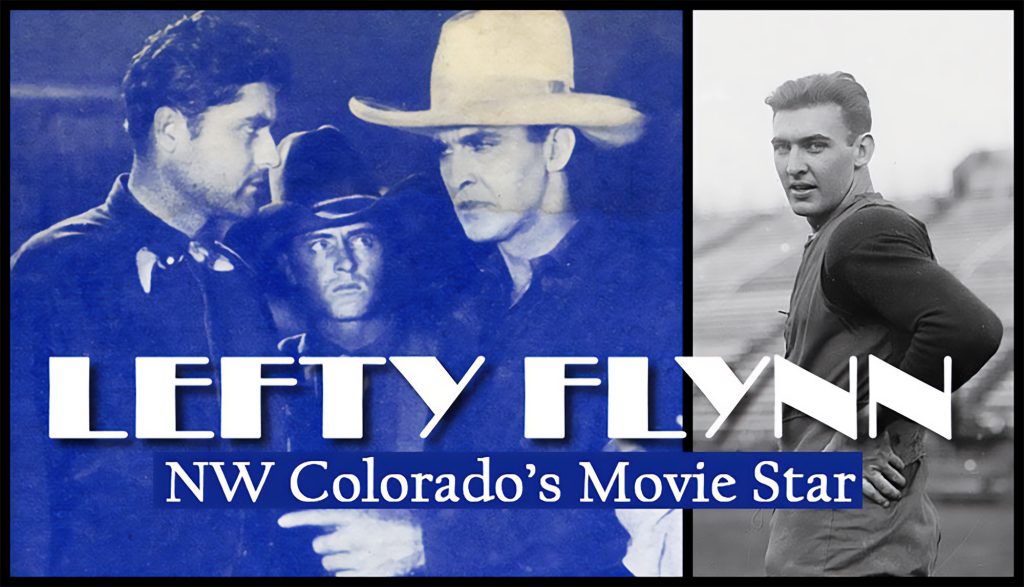

NW Colorado’s Silent Film Star

Maurice “Lefty” Flynn was one of northwest Colorado’s most colorful figures—a silent film star, standout athlete, musician, ladies’ man, and rancher. Born in 1892 in Connecticut, he became a 6’2″, 200-pound Yale football standout, earning the nickname “Lefty” for his left-footed kicking. After eloping with a chorus girl in 1913, he was expelled, beginning a long string of marriages.

Lefty and his father bought a 2,200-acre ranch east of Craig in 1915, where he charmed locals with music and athletic talent. After serving in World War I, he entered Hollywood with the help of novelist Rex Beach and quickly rose to stardom, appearing in 40 films from 1919–1927. In 1927 he briefly returned to ranching near Craig before resuming his globe-trotting lifestyle. Though he never lived in the area again, he fondly recalled his time in Craig in a 1958 Jubilee letter.

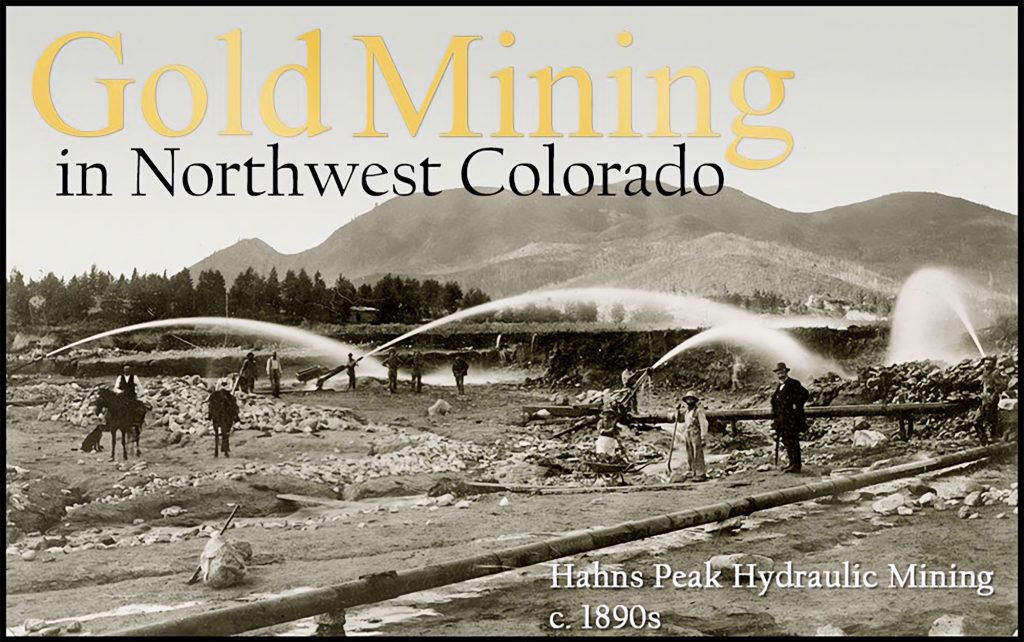

Gold in NW Colorado

Although Colorado’s major gold rush erupted in 1859, prospectors did not push into the far northwest until the mid-1860s. The region’s first documented discovery came in 1862 at Hahns Peak, which soon became the earliest official settlement in Northwest Colorado. Despite initial excitement, the true source of the gold was never located, and by the early 1900s the district was largely worked out. Additional discoveries in Routt County—such as those near Slavonia and the Gore Range—generated interest but never ignited a large-scale rush.

Still, these finds drew small groups of miners from established camps like Leadville and Georgetown, hoping for new fortunes. Once they arrived, however, most were met with the same stubborn obstacle: the area’s extremely fine, widely spread, flour-sized gold. Difficult to recover in profitable amounts, this gold ultimately prevented the region from developing the booming mining economy seen elsewhere in Colorado.

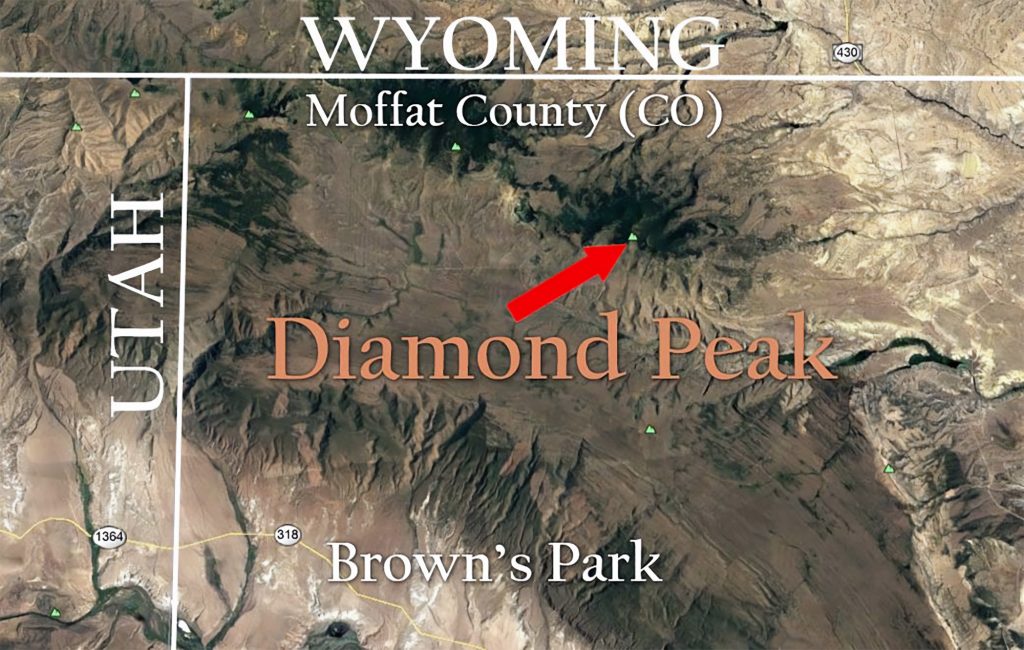

Great Diamond Hoax of 1872

In 1871, Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack stunned San Francisco financier George Roberts by dropping a bag of diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires on his desk—claiming they came from Northwest Colorado. Roberts brought in powerful investors and took the gems to Charles Lewis Tiffany, who appraised a fraction of them at $150,000. Convinced they had discovered a fortune, investors hired a mining engineer to inspect the site near today’s Diamond Peak. He declared it genuine, and Arnold and Slack collected $600,000.

But geologist and surveyor Clarence King doubted the find. After visiting in 1872, he discovered cut stones and other signs the site had been “salted” with imported gems. The hoax became international news. Arnold returned to Kentucky a wealthy man, while Slack died nearly penniless. King, credited with exposing the fraud, later became the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey.

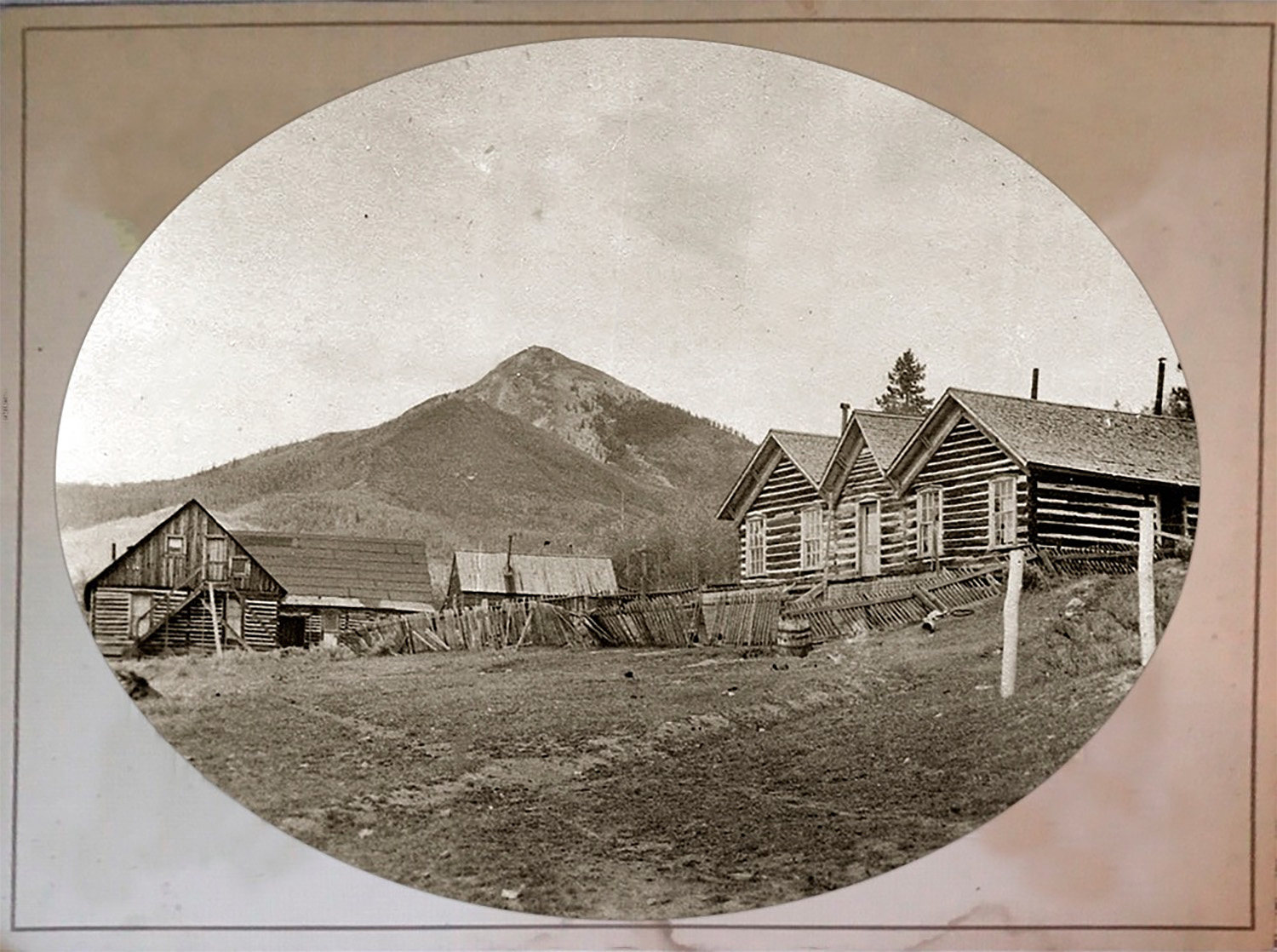

Steamboat’s Founding

James H. Crawford, a Missourian and Civil War veteran, is the founder of the town of Steamboat Springs. After first visiting the area in 1874, he settled his family near today’s library in 1875, and his cabin became the first building in the original settlement. In the early 1880s, Crawford, backed by businessmen from Boulder, formed the Steamboat Springs Townsite Company. This group successfully laid out the town’s grid of streets and alleys, transforming his homestead into the community that remains today. Despite tales of a fur trapper naming the area’s “chugging” spring, Crawford himself did not know who originally coined the name Steamboat Spring. However, it was already being used in the 1860s and possibly earlier. In fact, on his 1874 journey, Crawford ran into a fur trapper in Egeria Park (today’s Yampa, CO) who told him that if he were looking to settle down, he’d pick the area around the Steamboat Spring near the big westward bend on the Yampa River. This recommendation intrigued Crawford enough to make a detour that forever changed Yampa Valley history.

The Catastrophic Fire of 1939

In 1939, a catastrophic fire in Steamboat Springs took the lives of two people and destroyed northwest Colorado’s largest and most recognizable landmarks. The Cabin Hotel had been built in 1909 to coincide with the arrival of the railroad, marking Steamboat Springs’ long-awaited connection to modern transportation and tourism. The massive wooden structure stood across the Yampa River from the railroad depot—the site of today’s Bud Werner Memorial Library. Boasting 100 guest rooms, along with a spacious lobby, dining room, and full kitchen, the hotel dwarfed nearly every other building in the region. For decades it welcomed travelers, businessmen, and tourists from across the country and abroad, symbolizing progress and prosperity in the remote mountain town. On a cold January morning in 1939, the landmark vanished in roughly an hour. Investigators later blamed a faulty chimney flue. The loss left a permanent void in Steamboat Springs’ physical skyline and collective memory for generations that followed afterward.

1969- A Ski Resort is Born

In 1969, the purchase of the Steamboat Ski Resort by LTV Corporation marked a turning point in the resort’s history and in the future of Steamboat Springs itself. In fact, many people claim that you can measure the town of Steamboat Springs as before LTV, and after. Backed by deep corporate capital, LTV quickly shifted Steamboat from a regional ski hill to a nationally marketed destination. Within the first five years, aggressive advertising placed Steamboat alongside Colorado’s best-known resorts, dramatically increasing skier visits and national visibility.

That attention fueled immediate real-estate development. New condominiums, lodges, and second homes appeared near the base area, while land values rose sharply throughout the valley. Jobs tied to construction, hospitality, and resort operations expanded, driving steady population growth as workers and entrepreneurs relocated to Steamboat Springs.

Many of those early changes still shape the community today. National branding remains central to Steamboat’s identity, real-estate pressures continue to define housing debates, and the population growth sparked in the early 1970s set the trajectory for the modern resort town. LTV’s short-term investment produced long-lasting consequences that are still felt on and off the mountain.

The License Plates of WZ

n 1932, Colorado introduced a number system on license plates to identify the issuing county, with Routt County designated as “28.” That prefix was followed by a sequential number beginning with “1” and allowed plates to be traced directly to their home county. In 1959, the state abandoned the numeric system and adopted two-letter county codes, with Routt County assigned “WZ.” These plates quickly became symbols of local identity. Displaying one announced that you were “from here,” and owning a low-number plate often carried near-royalty status.

Until 1977, license plates were reissued every year and numbers were commonly reassigned, though some savvy owners managed to keep the same number year after year. That changed with the introduction of the five-year plate in 1977, when plates stayed with vehicles and were renewed using stickers. In 1982, Colorado shifted again, replacing two-letter codes with three-letter prefixes. Routt County plates became VXA through VXY, later narrowing to VXA through VXC in 1992. By 2000, county coding disappeared entirely, though a few proud survivors still roll the roads.

Hahns Peak: The Mountain with the Wrong Name

The Museum of Northwest Colorado in Downtown Craig has devoted extensive time to researching the long-standing confusion surrounding the name Hahns Peak. By examining historic newspapers in the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection, along with mining claims and family references, we sought to determine whether the name commonly associated with the peak is accurate.

The research points to prospector Joseph Henn, a German immigrant whose surname appeared in historical records under many spellings, including Henne, Hand, Hantz, and Hahn. These variations likely stemmed from pronunciation issues (Henn had a thick German accent) and inconsistent recordkeeping during the mining era. The museum located mining claims signed by Henn himself, as well as later newspaper articles in which family members attempted to correct the spelling.

One of the most significant sources is an 1895 Georgetown Courier article recounting the survival of William Doyle, who wintered with Henn in the mountains during 1866–67. That account clearly identifies Henn as the correct spelling. Doyle is also credited with naming the peak after his partner, though the incorrect version ultimately became entrenched.

Steamboat’s First Winter Carnival

Organized by Carl Howelsen, also known as the “Flying Norseman,” Steamboat Springs’ first Winter Carnival took place on February 12, 1914. Nearly 2,000 local spectators filled the streets and the jumps on Woodchuck Hill (where today’s college is) to witness what was then referred to as the Steamboat Springs Ski Carnival. While train delays limited Denver visitors to just twenty people, the enthusiasm of the community remained undimmed. The program began at 9:00 a.m. with the Steamboat Springs Gun Club gathering on the shooting grounds. Afternoon activities featured a half-mile race for boys using heavy wooden skis with hand-cut leather straps. Prior to Howelsen’s arrival, skiing had been primarily utilitarian; however, he introduced recreational jumping and racing. The carnival was built around ski jumping, cross-country racing, and novelty “street events”. Notable street competitions included skijoring, hurdle races, and ring-and-spear contests. On Woodchuck Hill, Howelsen himself won the professional jumping event with his longest jump of 108 feet. This overwhelming success led to the 1915 founding of the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club, established specifically to promote an annual carnival and recreational skiing. By the early 1940s, these traditions led to the town being labeled “Ski Town U.S.A.”. The photo show is a sterling silver ski trophy won by Marguarite McPhee, a Denver socialite and frequent visitor to Steamboat, during the very first Winter Carnival in 1914. Sadly, McPhee would die of the Spanish Flu just 4 years later.

Some Early Steamboat Olympians

Steamboat Springs, famously dubbed “Ski Town, U.S.A.,” has a long-standing tradition of producing world-class athletes, including many early Olympians. One of the most significant figures was Gordon “Gordy” Wren, who made history at the 1948 St. Moritz Olympics. He was the only American to qualify in four different disciplines: alpine, cross-country, jumping, and Nordic combined. Wren ultimately withdrew from the alpine events to focus on Nordic/jumping where his fifth-place finish was the best an American had ever achieved at the time.

Another legendary athlete, Marvin Crawford, was a standout multi-discipline skier who competed in Nordic combined at Cortina, Italy (1956). He was known for his versatility, famously winning every four-way competition he entered during his collegiate years.

The town’s Olympic legacy is perhaps best represented by the Werner siblings: Skeeter, Buddy, and Loris. Skeeter Werner competed in the 1956 Olympics finishing 10th in downhill. Her brother, Wallace “Buddy” Werner, was the first American alpine skier to be considered a true peer to elite European racers. He competed in the 1956 and 1964 games and was also selected for 1960 but could not compete due to injury. Today Mt. Werner and the town’s library are named in his honor. The youngest sibling, Loris “Bugs” Werner, represented the U.S. in both the 1964 and 1968 Olympics. Additionally, John Steele was one of the earliest pioneers, representing the U.S. in jumping during the 1932 Olympics.